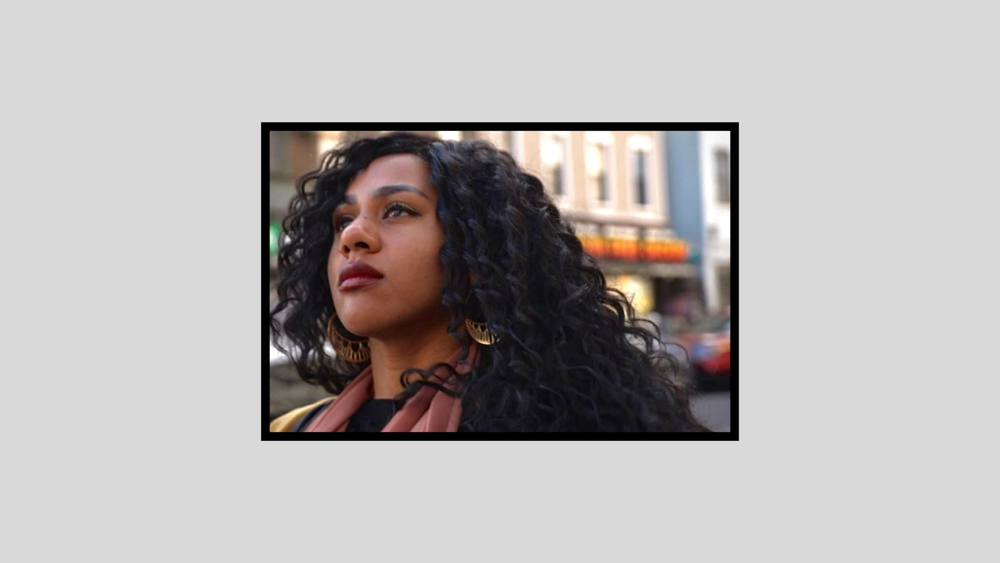

Will Spencer

The Paducah Sun

June 28, 2025

Used with permission

People are often interconnected with places across time, a key artistic tenet for Paducah native and poet Marissa Davis. Her west Kentucky upbringing influences her acclaimed debut book “End of Empire,” a collection of poems set to be published July 1 through Penguin Random House.

“It’s beyond words to describe how exciting it is,” Davis said. “I was first exposed to poetry in a contemporary way at the Kentucky Governor’s School for the Arts. Since I was 15, it’s been a dream to have a physical book like this for people to read and hopefully be moved by. I’m immensely grateful to be with an incredible publisher.”

After graduating from Paducah Public Schools, Davis attended Vanderbilt University and taught English in an elementary school in Paris. She then earned a Master of Fine Arts for poetry from New York University.

While her writing has appeared in several prestigious journals, Davis’ chapbook, “My Name & Other Languages I Am Learning How to Speak,” was selected for Cave Canem’s 2019 Toi Derricotte and Cornelius Eady Chapbook Prize.

With strides in the literary sphere, Davis returns to her roots for “End of Empire” to frame humanity’s complicated relationship with social institutions and the natural world. As the body becomes entangled with politics and communities are marginalized, she said the earth experiences a similar violence in the climate crisis.

Breaking narrative conventions and “allowing the sensory to speak for itself,” Davis’ words paint lush southern landscapes reminiscent of her childhood, including some that have since been devastated by disaster. She mentioned the December 2021 tornado in Mayfield and western Kentucky floods of 2023 as inspirations to a sweeping ecological framework.

“I was most interested in the world changing and how that’s affecting us,” Davis said. “People talk a lot about natural disasters when they happen to urban folks in big cities, but all across America, there are small towns suffering in their own ways.”

However, Davis said she intended to avoid a “borderline apocalyptic” tone and instead offer sentiments of hope through the regenerative power of nature. While those sublime forces illustrate how “to reclaim ourselves in the face of external hierarchies,” she said the poems chart an evolution in taking accountability for how humans transgress the planet.

“So much of the book is about what it means to be kind to the land we’re in and for that land to hopefully be kind to us in return,” Davis said. “Think of ourselves as a community, not only with one another but also the places we live. It grew outward from there. What are ways our actions affect each other across space and borders?”

Davis said those musings “spiraled into larger issues,” like systemic oppression in America and geopolitical strife overseas. She discussed how nature can be both turbulent and tranquil, paralleling the pursuit of peace and equality in periods of social upheaval.

She cited protests over George Floyd’s murder in 2020, as well as protests over the Israel-Palestine conflict at Columbia University last year, the latter of which happened while she was working at Barnard College. Davis said she strove for sensitivity in the tensions of Black, domestic and international identities.

“Racism affects us individually, physiologically and physically to the point that people sometimes lose their lives because of hatred,” Davis said. “Then there was thinking of how these struggles are connected across borders, like Palestine, Congo and Haiti. What does it mean to resist from where you are while being aware of struggles outside your own backyard?”

To achieve that extensive scope, Davis said she sought to weave a sprawling tapestry of biblical, mythological and historical references. She juxtaposed her personal experiences of girlhood in the Bible Belt against the more expansive canon of storytelling in the West, alluding to a foundational philosophy of creation that is sacred and tender.

“This idea is almost like a repentance for the sins we commit against the land. I found a lot of the trajectories in the Bible to be similar to Greek and Roman mythology,” Davis said. “I found it quite interesting to take those universal stories and find a specificity with them…making what is ancient something very present and immediate.”

Providing solace during distressing times, Davis said that art devises new means to process and re-envision the world past what is no longer tolerable. She emphasized how her style of poetry is fragmented in language but lyrically expressive in imagery, generating compact moments of profound resonance.

“Art invites us to imagine and believe in our own ability to enact pressure upon a world that can be different, more beautiful and kinder,” Davis said. “Poetry is the way in which you bring together so many different kinds of places and meanings. Fiction and prose are given a much larger span of space, but maybe not with the same kind of emotional punch a poem is capable of.”

Davis said she hopes her work challenges perspectives, igniting an enduring compassion and curiosity in approaching the fraught state of the world. She said her writing rhymes seemingly disparate elements to render a dynamic of empathy, where humanity’s greatest power resides.

“The heart of many poems is putting two apparently dissimilar things together and finding a connection,” Davis said. “I hope it allows us to learn and care enough to do something that makes us uncomfortable. I think the power lies in our hands, but we have to recognize ourselves as not powerless before we take the first steps of action.”

Similarly, Davis said her journey is defined by learning as a lifelong endeavor that bridges the gap between Paducah’s history and the vast possibilities of the rest of the world. She currently resides in Paris and is working toward a master’s degree in editorial, economic and technical translation at the Sorbonne Nouvelle.

“It’s been a whirlwind of joyous things, as far as what’s next for me,” Davis said. “What’s been really fun about being both abroad and studying languages is having the chance to dive into literature from other places on a broader scale to make it easily accessible back home.”